A Developer’s Guide to REST API Response Codes

When you're working with REST APIs, understanding response codes is non-negotiable. They're the standardized, three-digit numbers a server sends back to your application after it makes an HTTP request. Think of codes like 200 OK or 404 Not Found—they're a universal language for client-server communication, essential for building reliable and debuggable software.

Understanding The Role of REST API Response Codes

It helps to think of these response codes as a quick, structured conversation between your application (the client) and the server. When your app asks for something, the server doesn't just hand over the data. It also sends back a status code that gives you crucial context about how that request went. This whole system is what makes API interactions predictable and stable.

The codes are grouped into five distinct classes, each identified by its first digit. This simple categorization gives you an instant, high-level understanding of the response. For instance, any code starting with a 2 means success, while a 4 immediately points to an error on the client's end.

The Five Main Code Categories

This classification system makes troubleshooting and building application logic so much easier. As a developer, you can quickly pinpoint where a problem might be—is it a bad request from your app, or did something go wrong on the server?

To get started, here's a quick breakdown of what each category means.

Quick Reference to Response Code Categories

| Code Range | Category | General Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 100-199 | Informational | The request was received and is being processed. You won't see these often in everyday REST API work, but they're part of the standard. |

| 200-299 | Successful | The request was received, understood, and accepted. This is the green light you're looking for. |

| 300-399 | Redirection | The client needs to take another step to complete the request, usually by following a new URL. |

| 400-499 | Client Error | The request has bad syntax or can't be fulfilled. The problem is on the client's side, so the request may need to be fixed before trying again. |

| 500-599 | Server Error | The server couldn't fulfill a valid request. This points to an issue with the server itself, not the client's request. |

This table is a great starting point for diagnosing API behavior on the fly.

These standardized codes have been around since the early days of HTTP in the 1990s, with the official definitions refined over time in various RFCs, including the modern RFC 9110 (2022). You can learn more about this history of standardization and why having these conventions is so important for the web.

Handling Successful and Redirection Responses

When you get a 2xx response from an API, it’s a good thing. These are the "green lights" that tell you your request was received, understood, and processed without a hitch. But not all successes are created equal, and the specific code you get back can tell you a lot about what just happened on the server.

On the other hand, 3xx redirection codes aren't errors, either. They're more like a "detour" sign, telling your client that it needs to take another step to finish the request. This usually means the resource you're looking for has moved. Knowing how to handle both of these categories is a fundamental part of building a robust application.

Mastering 2xx Successful Responses

The 2xx series of codes confirms that the client's request was successful. While a 200 OK is the one you'll see most often, getting more specific with codes like 201 Created or 204 No Content makes your API much clearer and easier for other developers to work with.

200 OK This is the classic, all-purpose "everything worked" code. It’s the standard response for a successful

GETrequest that fetches data or aPUTthat updates an existing resource. For instance, aGET /users/123call should come back with a 200 OK and the user's information right in the response body.201 Created A 201 is more precise than a 200. It confirms that not only was the request successful, but a brand-new resource was created as a result. This is the correct response for a

POSTrequest that adds something new, like creating a new user account. A proper 201 response should also include aLocationheader pointing to the URL of the newly created resource.204 No Content This one tells you the server did its job successfully but has nothing to send back in the response body. Think of a

DELETErequest—when you ask to delete a blog post withDELETE /posts/45, a 204 is the perfect way for the server to say, "It's gone," without sending any unnecessary data.

Key Takeaway: Choosing the right 2xx code makes an API more intuitive. A 201 explicitly confirms creation, while a 204 confirms an action is complete without a payload, which helps cut down on data transfer.

Navigating 3xx Redirection Codes

Redirection responses are the API's way of saying, "The thing you're looking for isn't here anymore, but I know where it is." The client is expected to follow the new URL provided in the Location header. The key is knowing whether that move is permanent or just for now.

301 Moved Permanently This code is a big deal, especially for SEO and API versioning. It means the resource has been moved to a new URL for good. Search engines and browsers will update their indexes and bookmarks, sending all future traffic directly to the new location. It's the right choice when you're restructuring your URLs and want everyone to follow along automatically.

302 Found (and 307 Temporary Redirect) A 302 Found indicates a temporary move, but it has a bit of a messy history. Early on, some clients would incorrectly change the request method from

POSTtoGETwhen they received a 302, which could cause all sorts of problems.To clear up that ambiguity, 307 Temporary Redirect was introduced. It strictly instructs the client to retry the exact same request at the new URL, without changing the method. If a

POSTrequest gets a 307, the client knows to make anotherPOSTto the new location. This makes the 307 a much safer and more predictable option for temporary redirects, like when a server is down for maintenance.

Navigating 4xx Client Error Codes

When your API returns a response code in the 4xx range, it's essentially pointing a finger back at the client. The server is telling you, "I heard you, but I can't do what you're asking because the request itself is flawed." These codes are your first and best clue for debugging issues that originate from your application, not from a server meltdown.

Unlike the dreaded 5xx server errors, a 4xx code is something you, the client developer, can actually fix. The server has done its job by catching an invalid request. Now it's on you to correct it and try again. Getting comfortable with these responses is fundamental to building a resilient application that can gracefully handle bad inputs, authentication problems, or other client-side slip-ups.

400 Bad Request

The 400 Bad Request is the classic catch-all for client-side problems. It’s the server’s way of saying it couldn’t make sense of your request due to some kind of error on your end. This could be anything from a typo in your JSON to sending parameters in the wrong format.

Common culprits behind a 400 Bad Request often include:

- Malformed JSON or XML: A simple syntax error, like a missing comma or a misplaced bracket in the request body.

- Invalid Parameters: Sending a string where the API expects a number, or vice versa.

- Request Size Too Large: The payload you're sending exceeds a limit set by the server.

Pro Tip: If you hit a 400, the first thing to do is meticulously review the request you sent. Compare your payload, headers, and URL parameters against the API documentation. The mistake is almost always a subtle mismatch.

401 Unauthorized And 403 Forbidden

It's easy to mix these two up, but they address very different security scenarios. A 401 Unauthorized response means your request lacks valid credentials. In short, the server doesn't know who you are because you haven't logged in or provided a correct API key.

On the other hand, a 403 Forbidden means the server does know who you are—it successfully authenticated you—but has determined you don't have permission to access that specific resource. You're logged in, but you're not on the guest list for that particular party. We cover this in more detail in our guide to handling the HTTP status code 401.

Here’s a simple way to think about it:

| Code | Meaning | Example Scenario |

|---|---|---|

| 401 Unauthorized | Authentication is missing or failed. The server doesn't recognize you. | You try to fetch /profile without including a valid token in the Authorization header. |

| 403 Forbidden | Authentication succeeded, but you lack permissions. The server knows you, but says you can't come in. | A user with a "viewer" role attempts to access an admin-only endpoint like /admin/users/delete. |

404 Not Found

The 404 Not Found is probably the most famous HTTP status code on the internet. It simply means the server looked for the resource at the URL you provided and came up empty. This is a client-side error because you're asking for something that isn't there.

This can happen for a few common reasons:

- A typo in the URL: You're requesting

/user/123when the endpoint is actually/users/123. - The resource was deleted: The data you're asking for, like a specific customer record, used to exist but has been removed.

- An incorrect endpoint path: Your application might be calling an outdated or entirely wrong API endpoint.

A 404 isn't a sign that the server is broken. It's a perfectly valid response from a healthy server that just can't find what you asked for.

Other Important 4xx Codes

While the ones above are the most common, a handful of other 4xx codes give you even more specific feedback, which can make debugging a lot faster.

405 Method Not Allowed: You'll see this when you use an HTTP method that the resource doesn't support. For instance, trying to

POSTdata to a read-only endpoint that only acceptsGETwill trigger a 405. A well-behaved API will include anAllowheader in the response, listing the supported methods (e.g.,Allow: GET, PUT).409 Conflict: This code signals that your request can't be processed because it conflicts with the resource's current state. The most common scenario is trying to create a new user with an email address that's already registered in the system.

429 Too Many Requests: This is all about rate limiting. The server is politely telling you to slow down because you've sent too many requests in a short period. Good APIs will also include a

Retry-Afterheader telling you exactly how long to wait before trying again.

The only way to ensure your application can handle these situations gracefully is to test them. Using a tool like dotMock, you can easily create mock endpoints that return specific 4xx codes on demand. This lets you build and verify your error-handling logic for everything from bad requests to rate limits, all without needing a live backend. It's a crucial step in developing robust software that delivers a great user experience, even when things don't go as planned.

Troubleshooting 5xx Server Error Codes

Unlike the 4xx errors that point a finger back at the client, the 5xx series of REST API response codes signals a completely different kind of problem. When you get a 5xx response, it means your request was likely valid and well-formed, but the server itself simply couldn't fulfill it. The issue is entirely on the server-side, so tweaking your request won't fix anything.

For developers on the client-side, these errors can be a real headache because they often feel like a black box. You know your code is right, but the API keeps failing. Getting a handle on what these codes mean is the first step toward diagnosing the issue and communicating effectively with backend teams or the API provider.

500 Internal Server Error

The 500 Internal Server Error is the most generic, catch-all server error you'll see. It’s the server’s way of throwing its hands up and saying, "Something went wrong, but I have no idea what." This code is used for any unexpected condition that pops up and prevents the server from processing the request.

When a client receives a 500 error, the best immediate action is to stop and wait. Hammering the server with the same request will probably just trigger the same error and could put more strain on an already struggling system.

What usually causes a 500 on the server?

- A bug or unhandled exception in the application code.

- The database connection failing or timing out.

- Permission issues or problems with server-side scripts.

From a Developer's Perspective: If you hit a 500 error, check the API's status page first. If nothing's reported, it's time to file a bug. For backend developers, solid logging is your best friend for quickly tracking down the root cause of these unexpected failures. We have a whole guide dedicated to this common issue, which you can read here: What Is an HTTP 500 Error?.

502 Bad Gateway

A 502 Bad Gateway error is far more specific. This code means your request hit a server that acts as a gateway or proxy, but that server received a junk response from an upstream service it needed to talk to. Think of it as a chain of command: your request might go to a load balancer, which then passes it to an application server. If that application server is down or sends back a garbled response, the load balancer will return a 502.

This is fundamentally a networking-related server error. The first server you contacted is fine, but one of its dependencies is not. You’ll often see this in microservices architectures or any system that relies heavily on third-party APIs.

503 Service Unavailable

The 503 Service Unavailable response is a clear message that the server is temporarily out of commission. This isn't always a "bug" in the traditional sense; it's often a deliberate status indicating the server is offline for maintenance or completely overloaded with traffic.

Unlike a 500 error, a 503 can be intentional. A well-designed API will return a 503 during a planned deployment or if it gets hit with a traffic spike that exceeds its capacity.

When you get a 503, here's how to handle it on the client-side:

- Look for the

Retry-Afterheader: The response might include this header, which tells you exactly how many seconds to wait before trying again. - Use exponential backoff: If there's no

Retry-Afterheader, the smart move is to implement a retry strategy. Wait a short period (like 1 second), then double that wait time for each subsequent failure (2s, 4s, 8s, etc.) to avoid dogpiling the server.

Sometimes, server-side issues leading to 5xx errors require direct intervention, where understanding procedures for safely rebooting servers becomes an essential part of the recovery process.

Simulating 5xx Server Errors with dotMock

For both frontend developers and QA engineers, testing how your application behaves during a server outage is non-negotiable if you want to build a resilient product. You have to make sure your app can handle these scenarios gracefully—maybe by showing a friendly error message instead of just crashing.

With a tool like dotMock, you can spin up mock API endpoints that simulate these server-side failures on demand. This lets you get ahead of the problem.

Here's what you can do:

- Test Retry Logic: Set up an endpoint to return a 503 Service Unavailable. This is perfect for verifying that your application's exponential backoff mechanism actually works as intended.

- Verify Error States: Simulate a 500 Internal Server Error to confirm your UI shows the right error message and doesn't leave the user stuck in a broken state.

- Build Resilient Systems: By testing these failure modes in a safe, controlled environment, you can build applications that stay stable and predictable even when their backend services are having a bad day.

Best Practices for API Response Design

Knowing the different REST API response codes is one thing, but actually designing and consuming them thoughtfully is what separates a frustrating API from a great one. For those of us building APIs, the goal is always predictability and clarity. For those on the consuming end, it’s all about resilience.

A well-designed API response is more than just data; it’s a clear, reliable conversation between services. It should be consistent, specific, and give developers enough context to fix problems without having to dig through server logs. Getting this right reduces friction and just makes development faster for everyone.

For API Providers

When you're designing an API, every response needs to be crystal clear, especially when things go wrong. A vague error message is a dead end for any developer trying to use your service.

- Use Specific Codes: Don't fall into the trap of using a generic

400 Bad Requestfor every client-side problem. A409 Conflictis far more helpful for a duplicate entry, and a405 Method Not Allowedinstantly tells a developer they've used the wrong HTTP verb. Be precise. - Create Useful Error Bodies: An error code alone is rarely enough. A truly useful error response is a JSON object with key details: a unique error ID for tracking, a clear message for the developer, and maybe even a link to the relevant docs.

- Maintain Consistency: Your API’s response structure should be predictable. If your success responses follow a specific JSON format, your error responses should, too. This consistency makes it much easier for developers to write solid client-side parsing and handling logic.

Thoughtful API response design is also a major focus during security code reviews, as it helps prevent sensitive information from leaking out in error messages. For a much deeper look, check out our guide on the best practices for API design, where we cover these ideas in more detail.

For API Consumers

When you’re building the client-side application, the game is all about building something that can handle API failures gracefully. You have to assume things will go wrong and code defensively.

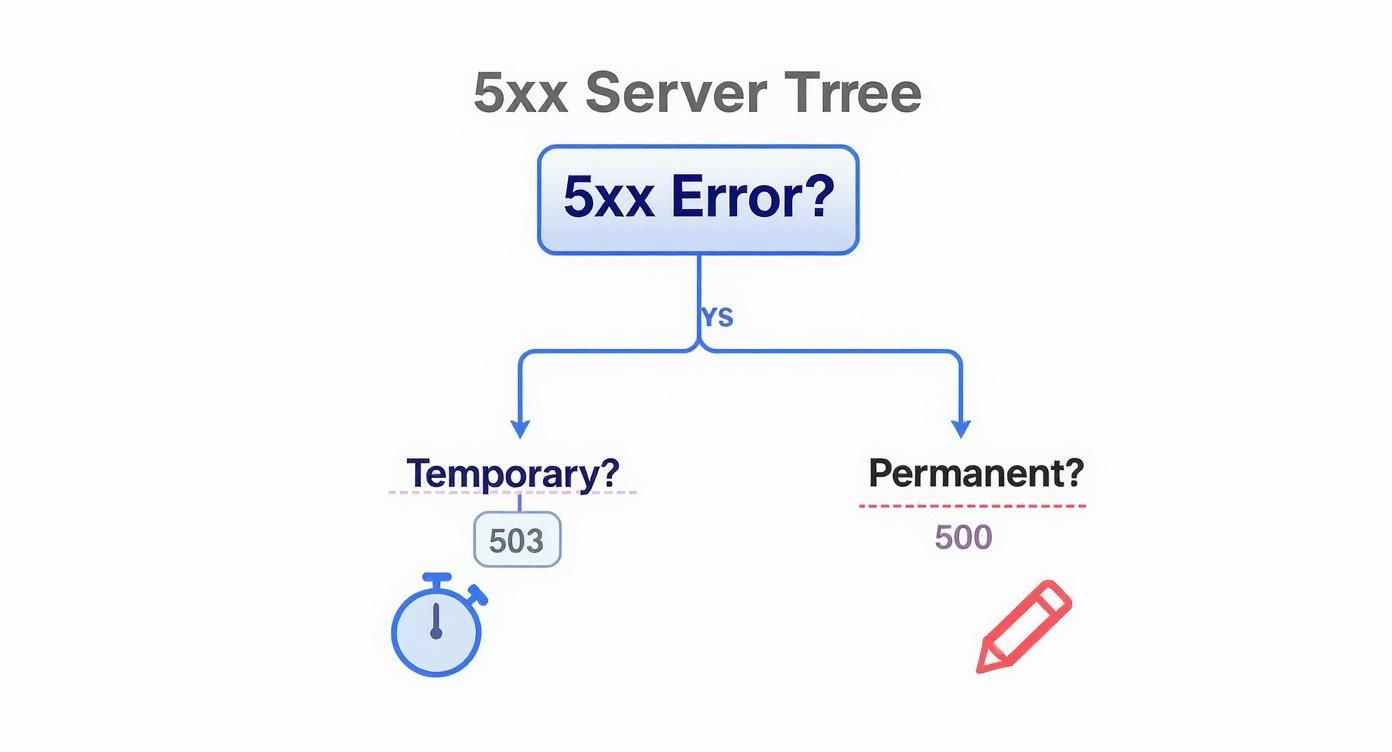

This decision tree illustrates how a client could handle 5xx server errors, showing the difference between a temporary issue that’s worth a retry and a more permanent one that isn't.

The big takeaway here is that not all server errors are created equal. A 503 Service Unavailable is a strong hint to try again later, whereas a 500 Internal Server Error often points to a more serious, lasting problem on the server.

To build this kind of resilient application, here are a couple of tactics:

- Implement Global Error Handlers: Instead of littering your code with

try/catchblocks for every single API call, set up a centralized handler to intercept responses. This handler can check status codes and direct them to the right logic, whether that’s showing a user a notification or just logging the error for your team. - Use Retry Mechanisms Wisely: For temporary server errors like a

503 Service Unavailableor a rate-limiting429 Too Many Requests, retrying the request automatically is a great strategy. Just be sure to implement an exponential backoff approach—waiting a little longer between each retry—to avoid hammering an already struggling server.

Common Questions About API Response Codes

When you're deep in API development, a few status codes tend to cause the most head-scratching. Understanding the subtle but critical differences between them is the key to building resilient, predictable applications. Let’s clear up some of the most common points of confusion.

401 Unauthorized vs. 403 Forbidden: What’s the Real Difference?

It’s easy to mix these two up since they both deal with access control, but they signify completely different problems.

A 401 Unauthorized response means authentication is the issue. The server either didn't receive any credentials or the ones provided were invalid. Essentially, the server has no idea who you are.

On the other hand, a 403 Forbidden response means the server knows exactly who you are—your credentials are valid—but you simply don't have permission to perform the requested action. Your identity is confirmed, but your access level isn't high enough.

Think of it this way: a 401 is like being denied entry to a building because you forgot your ID. A 403 is when you show your valid ID, but the guard checks a list and says, "Sorry, you're not authorized to enter this specific floor."

When Should I Use 201 Created Instead of 200 OK?

This is another classic question. Both 200 OK and 201 Created signal success, but each has a specific job to do when it comes to changing resources on the server.

200 OK: This is your go-to success code for most operations. It's perfect for requests that successfully retrieve data (GET) or update an existing resource (PUTorPATCH). If you asked for a user's profile and got it, or you updated their email address,200 OKis the right response.201 Created: Save this one for a very specific case: when a request successfully creates a brand-new resource. The classic example is aPOSTrequest to an/articlesendpoint that results in a new article being added to the database.

For a truly RESTful API, a 201 response should also include a Location header. This header should contain the URL pointing directly to the newly created resource, making your API more intuitive for clients.

How Should My App React to a 503 Service Unavailable?

Receiving a 503 Service Unavailable code is a clear signal that the server is temporarily out of commission. This could be due to planned maintenance or, more commonly, because it's overloaded with traffic. The key here is that the problem is temporary.

The standard way to handle a 503 is to implement a retry strategy with exponential backoff. Don't just hammer the server with immediate retries. Instead, wait a moment, then try again. If it fails again, double the waiting period before the next attempt. This gives a struggling server a chance to recover.

Also, be sure to check the response for a Retry-After header. If it’s present, the server is giving you a specific time to wait before your next attempt. Always respect it.

Testing how your application handles these nuanced scenarios is crucial for reliability. With a tool like dotMock, you can easily set up mock API endpoints to return any HTTP status code you need. This lets you thoroughly test your error handling for 401s, 503s, and everything in between without depending on a live, and potentially flaky, backend.